Asmara is the capital city of the NE African country Eritrea. Asmara has a many-sided geopolitical history. In 1882, Italian colonists began their occupation of Eritrea. Over sixty years they asserted their presence, filling its capital city, Asmara, with superlative art deco architecture and experimental early modernist design.

In the 1940s Italy was replaced by British and then Ethiopian ruling interests. Finally in 1991, after a 30 year war for independence, the modern State of Eritrea slowly transitioned to a normalized state.

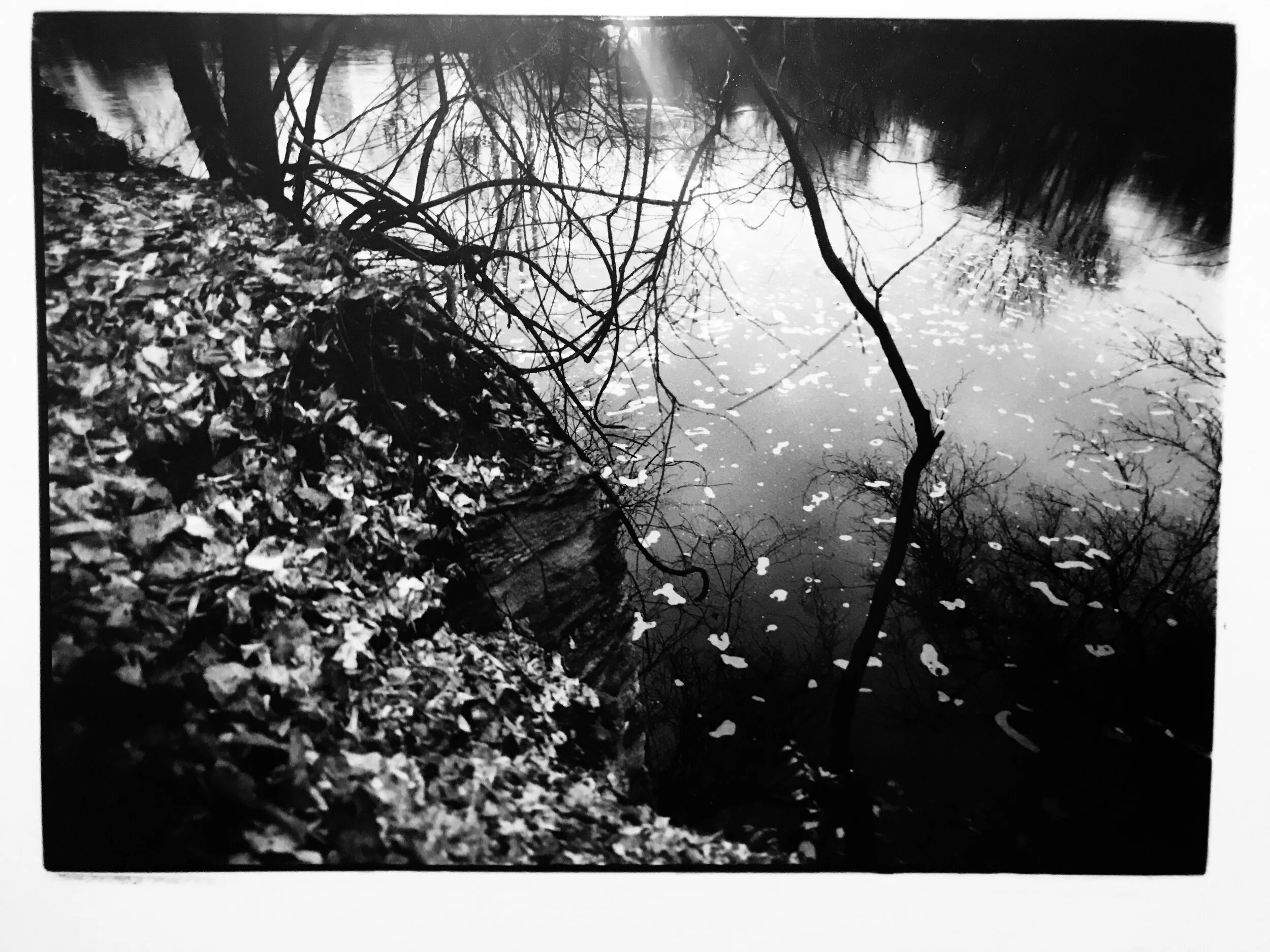

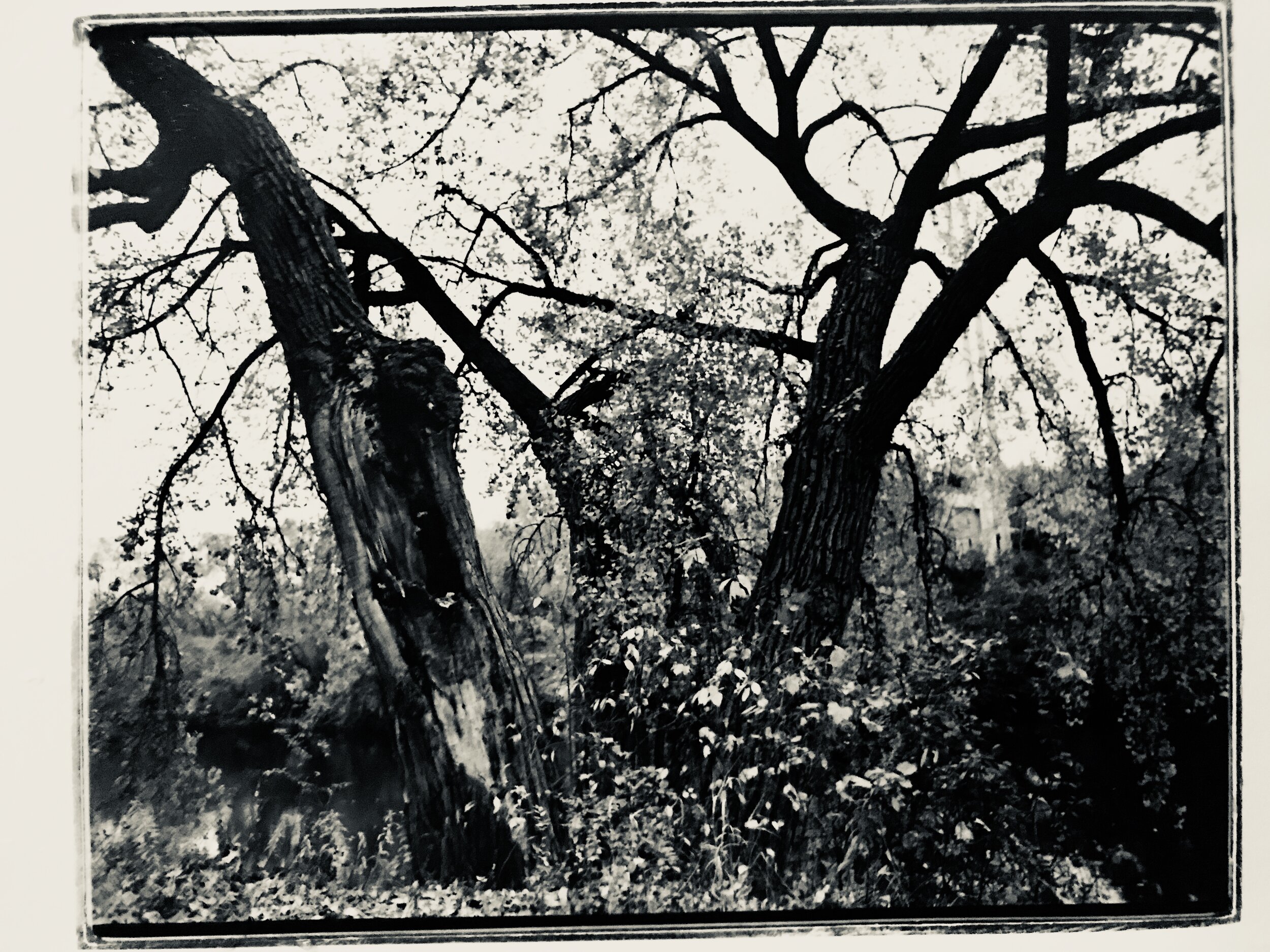

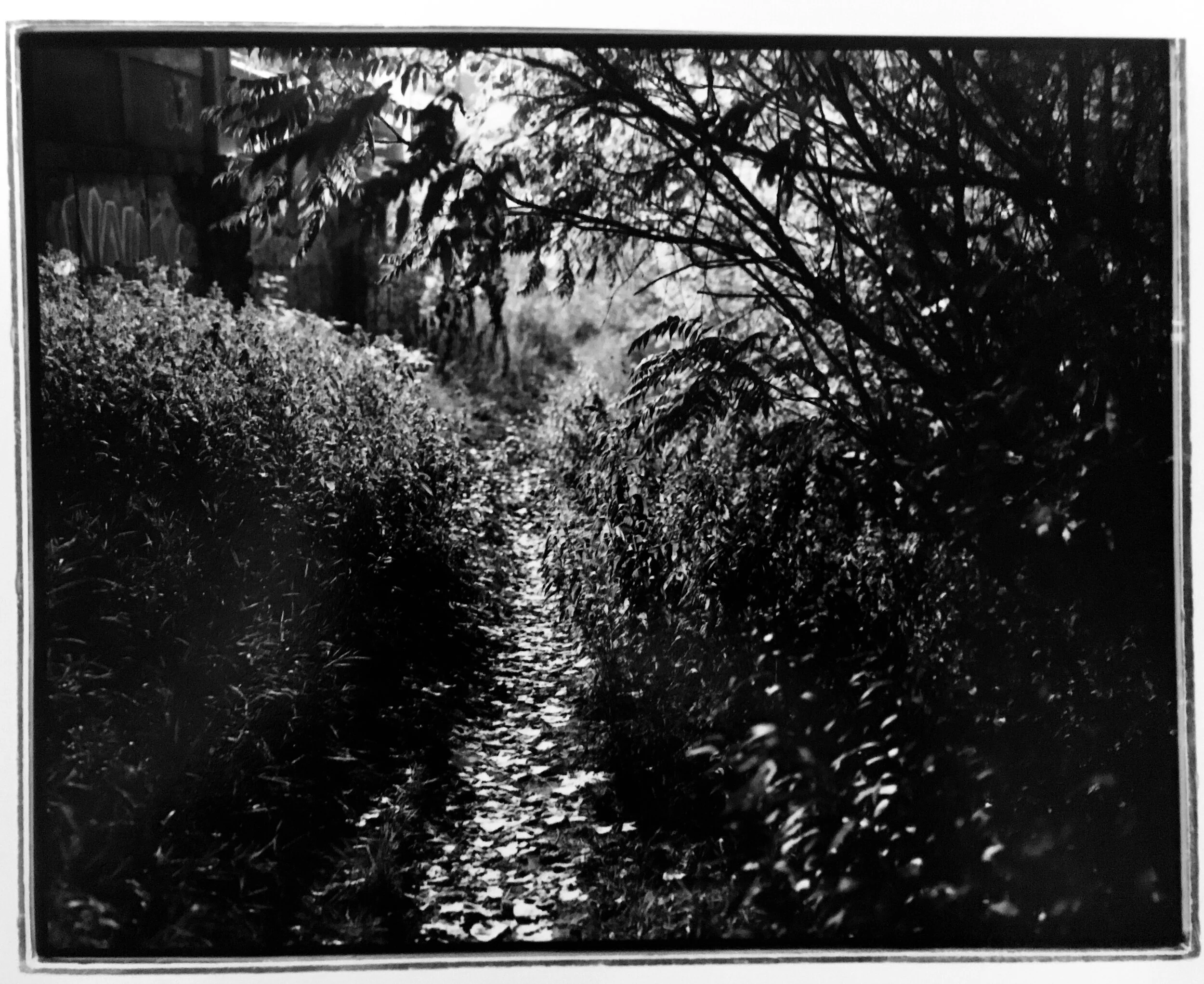

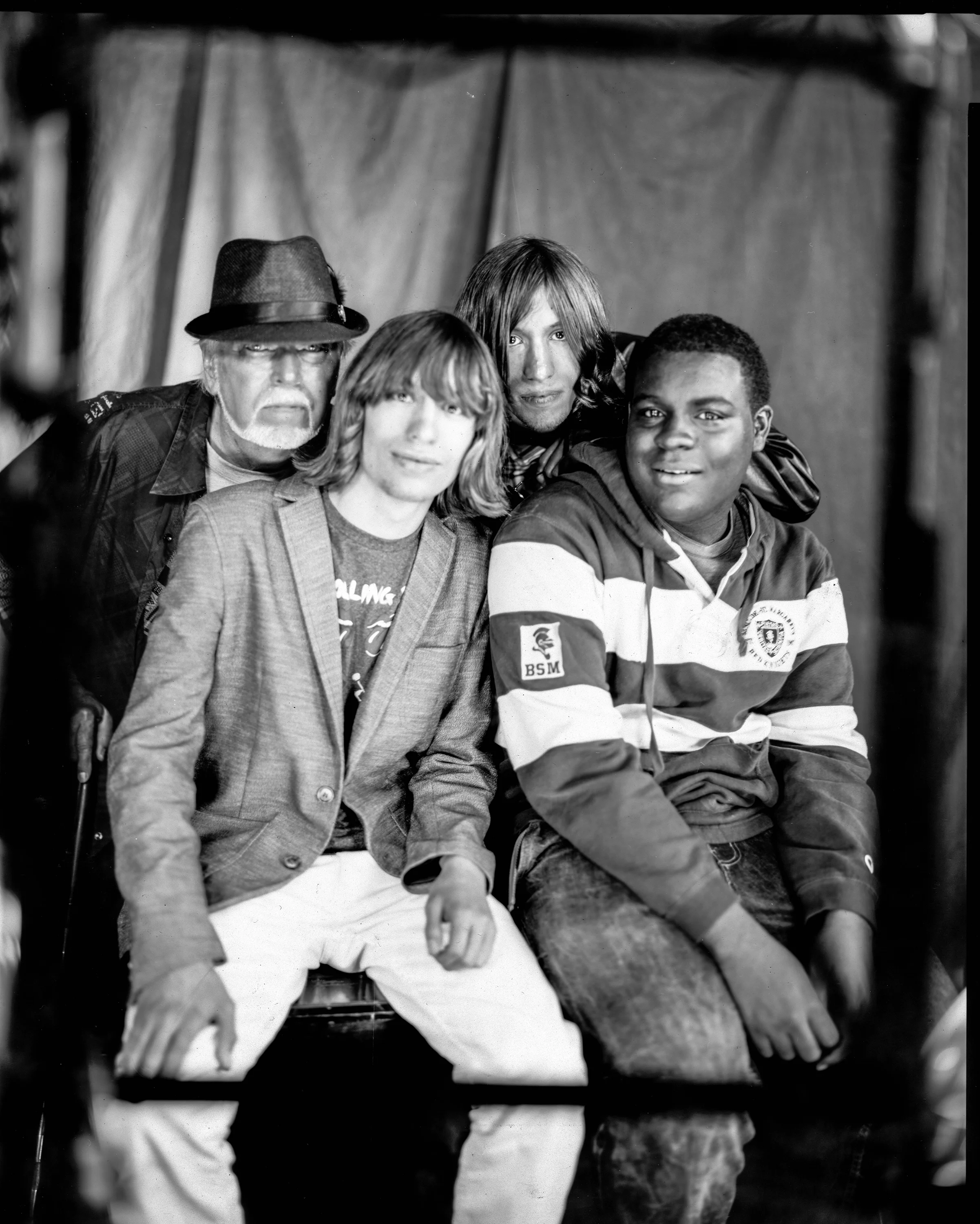

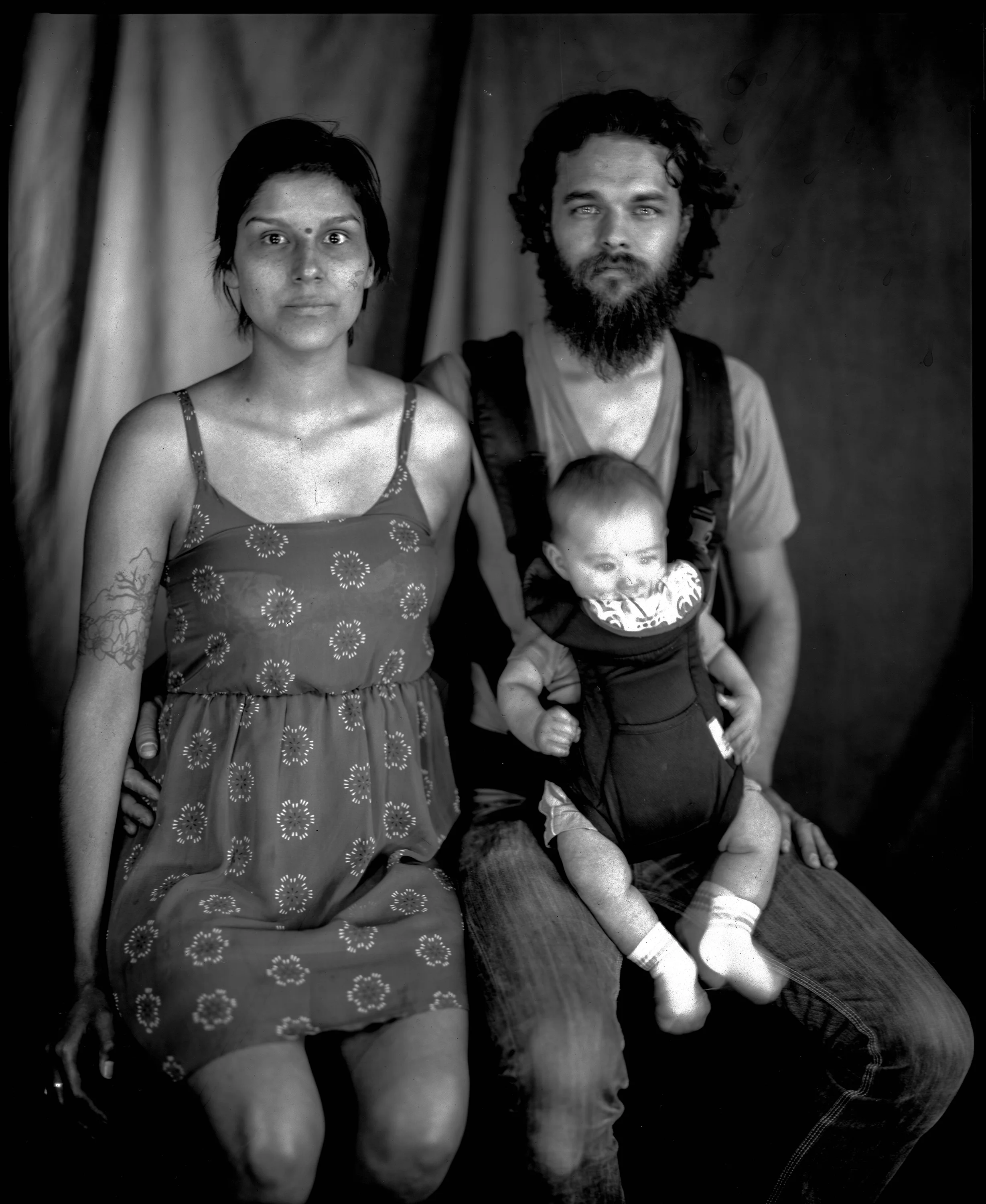

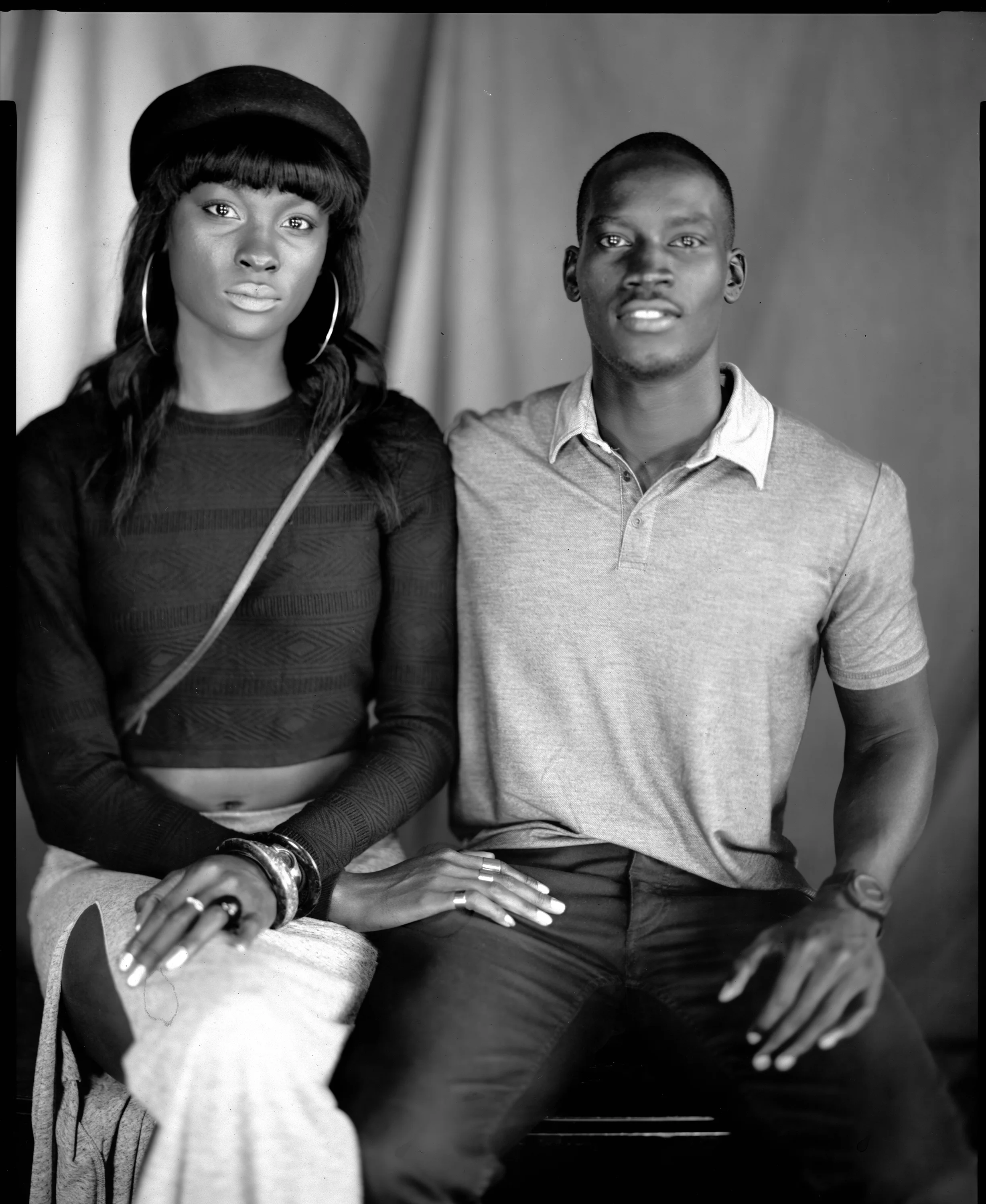

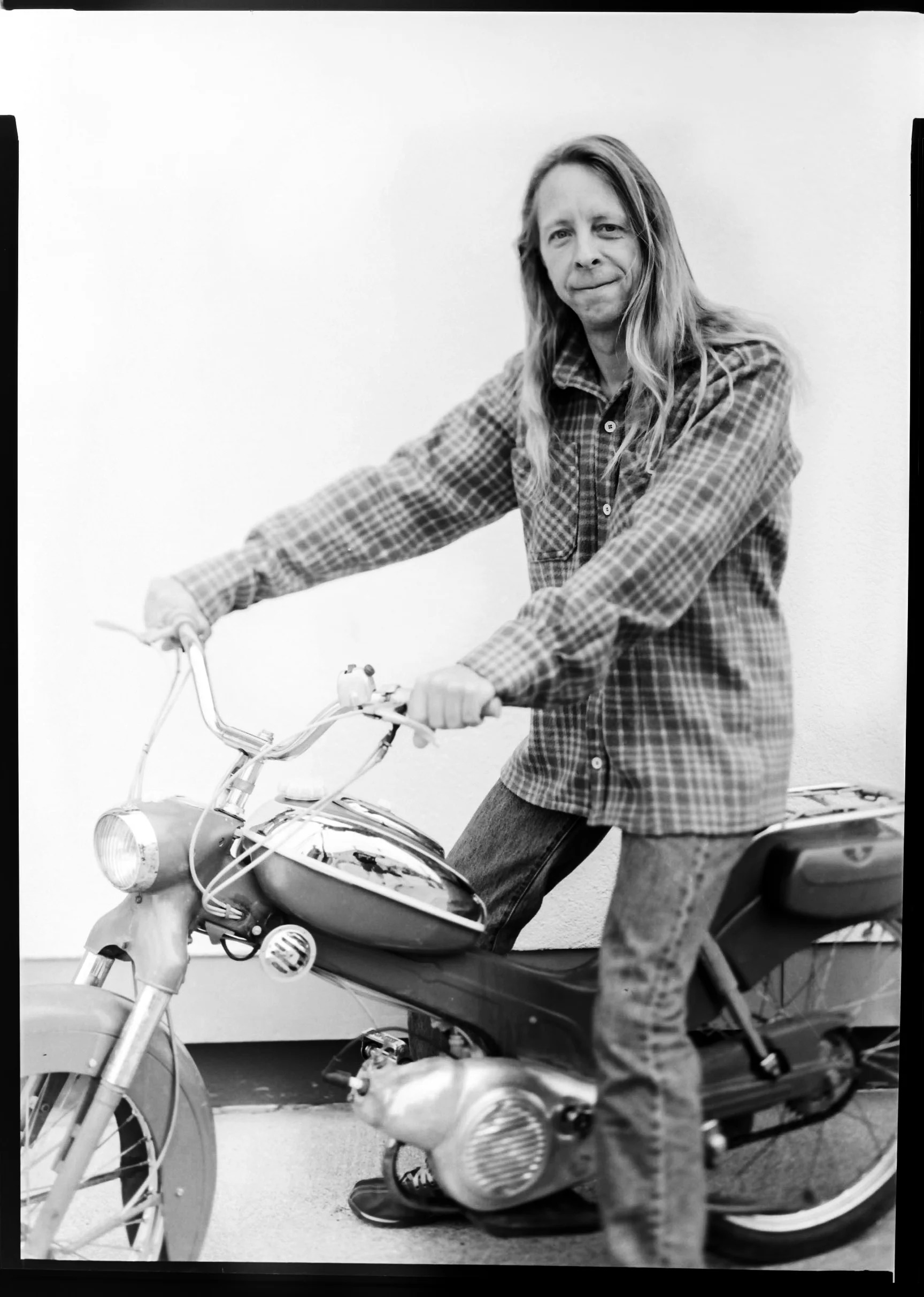

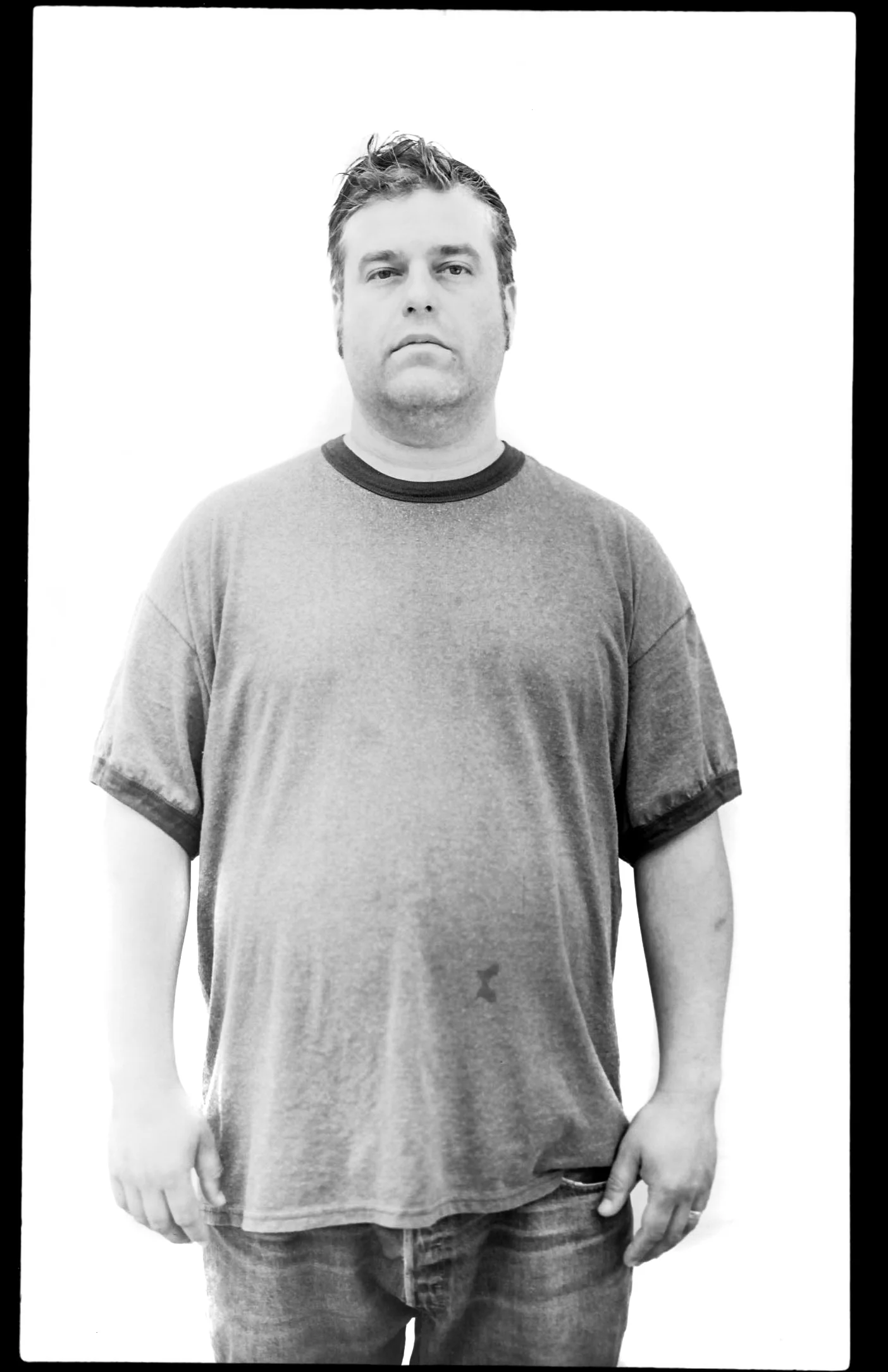

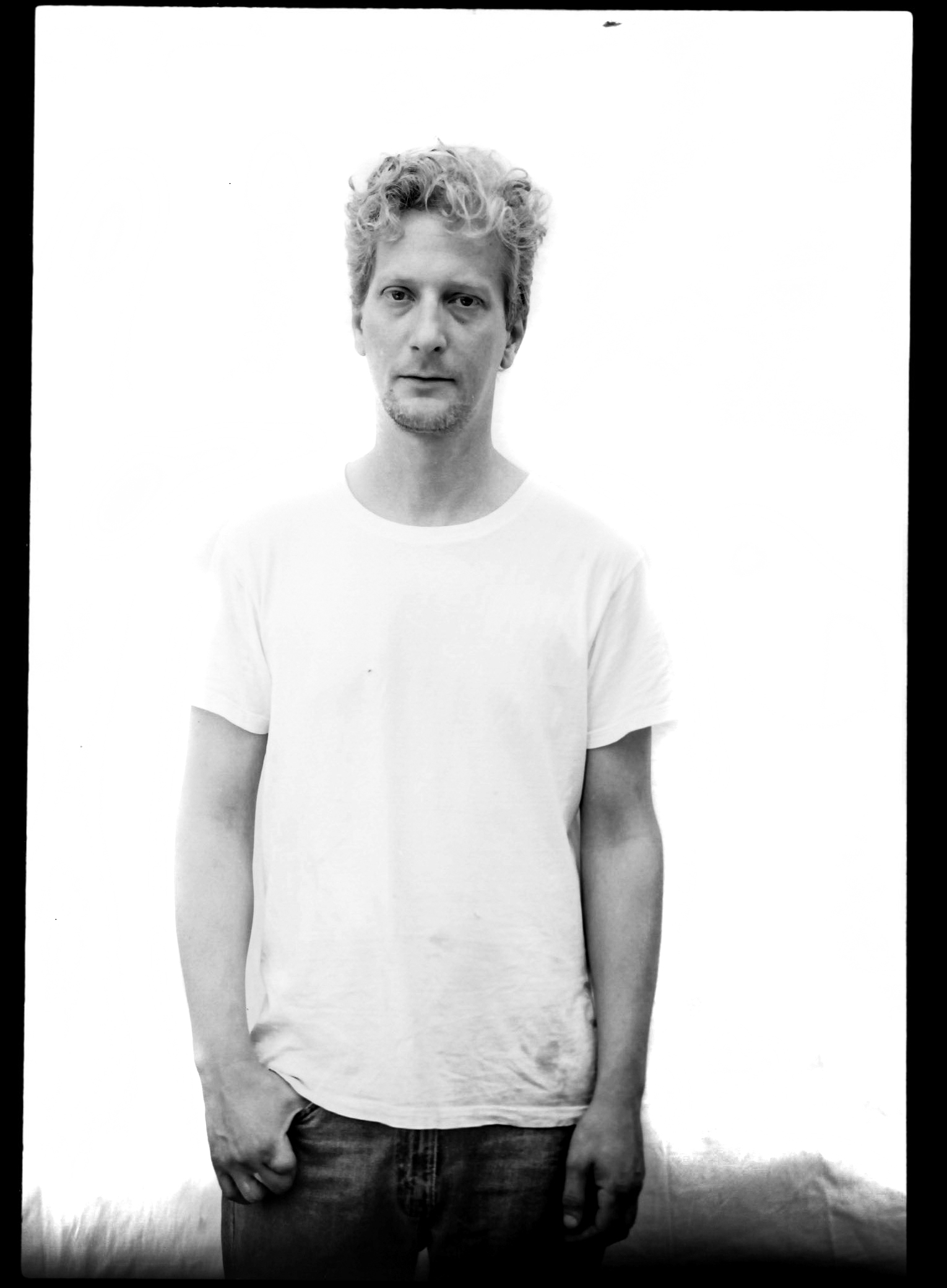

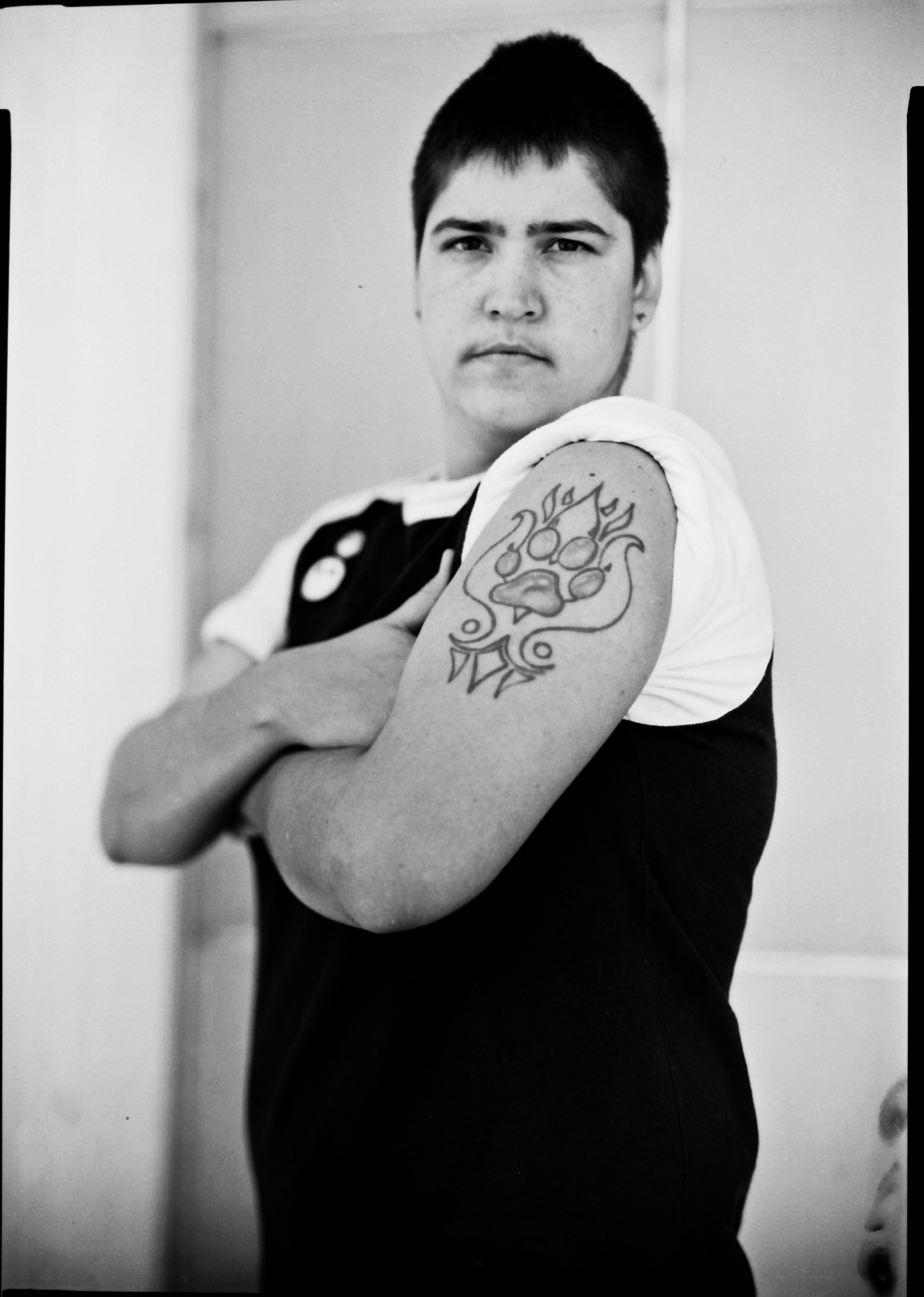

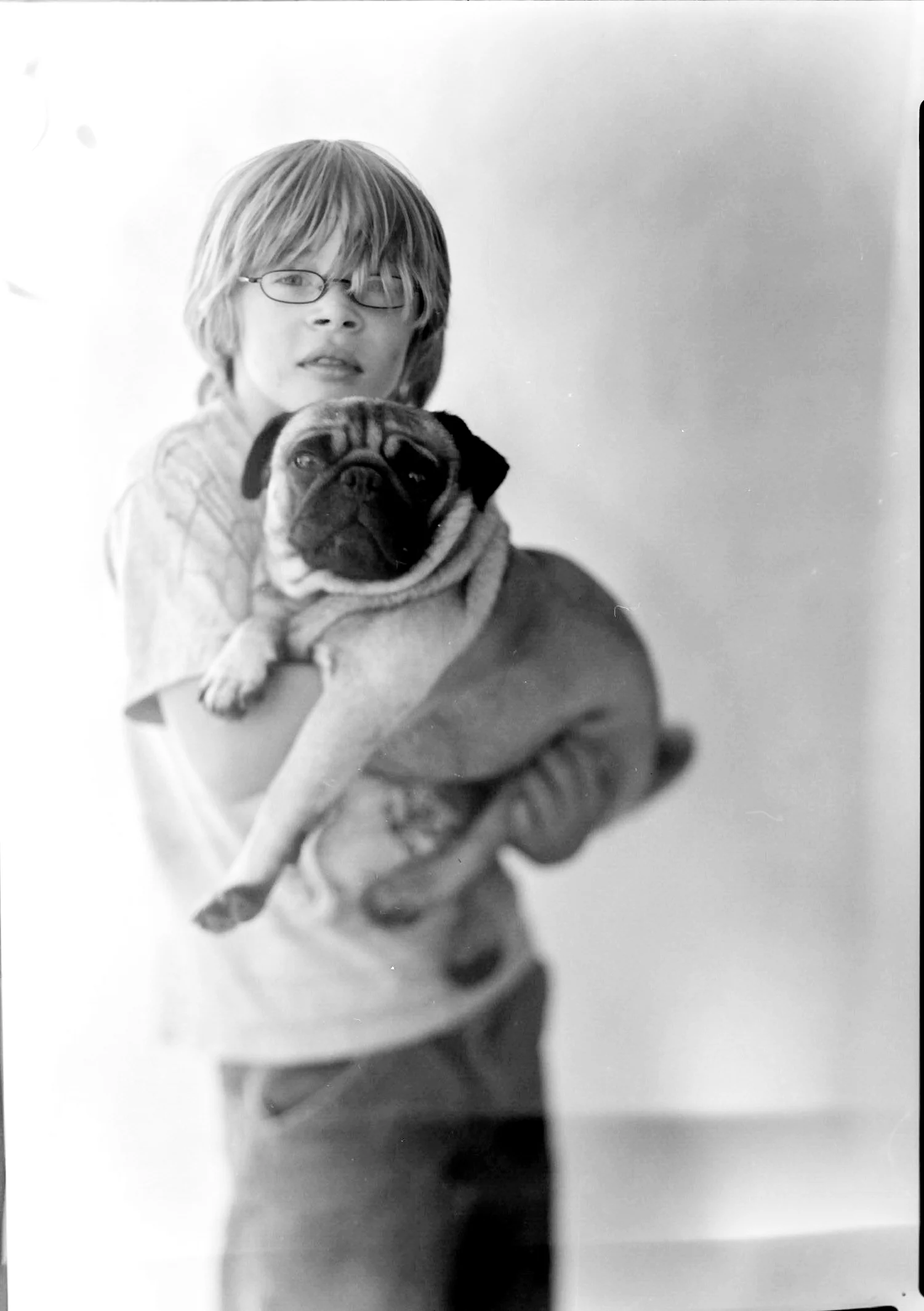

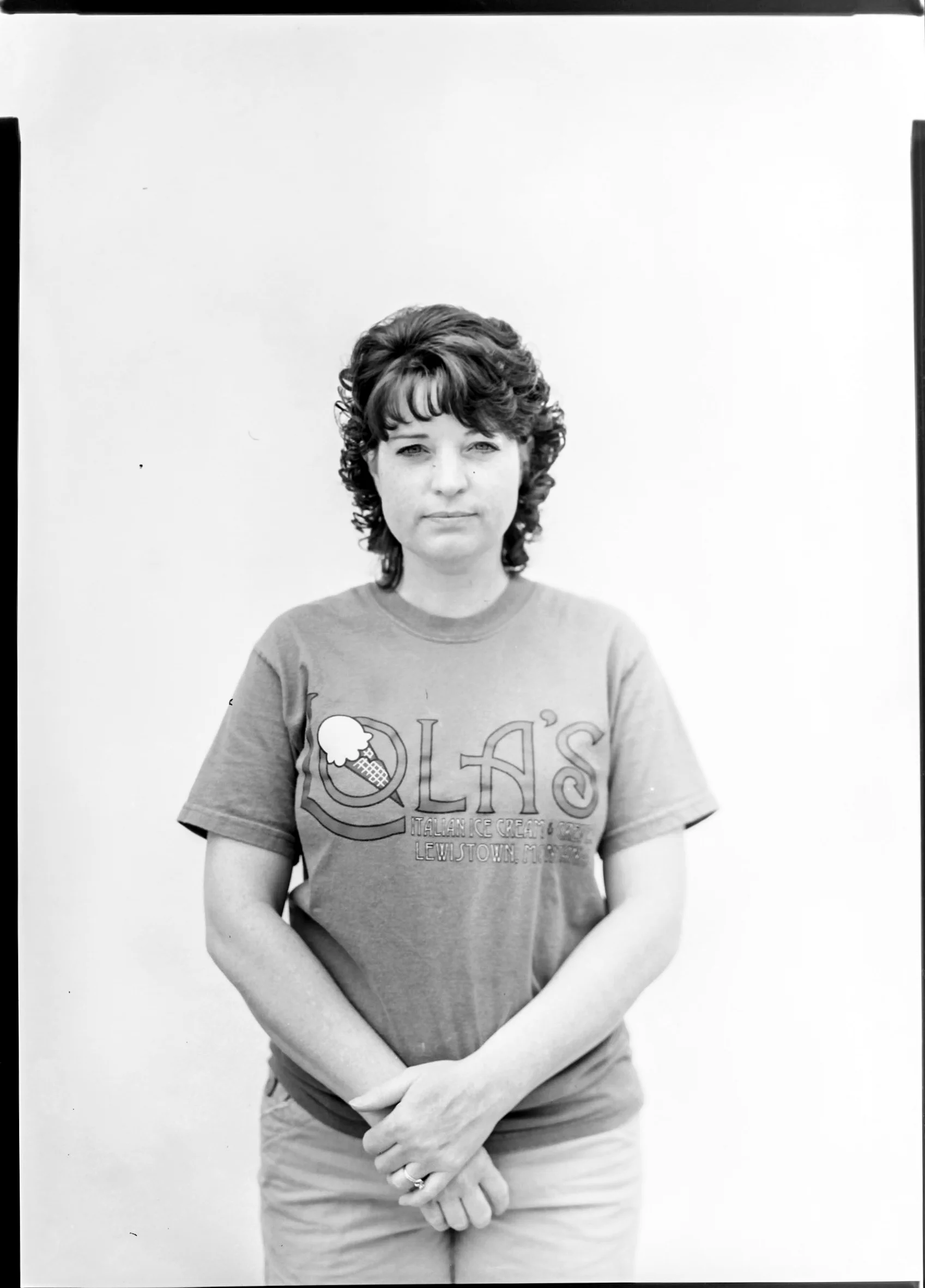

My work is framed by this distressed history, and the urban landscapes upon which this history is impressed. Despite generations of conflict and subjugation, the people of Eritrea that I've come to know remain optimistic and fiercely proud of their survival amid such struggles. Asmara's unique, at times incongruous infrastructure is amazingly well preserved, reflecting the heartfelt hope that I hear from its citizens. In selecting serval photographs from a substantial reservoir, I've attempted to portray both Asmara’s rich past, and it’s uncertain future.

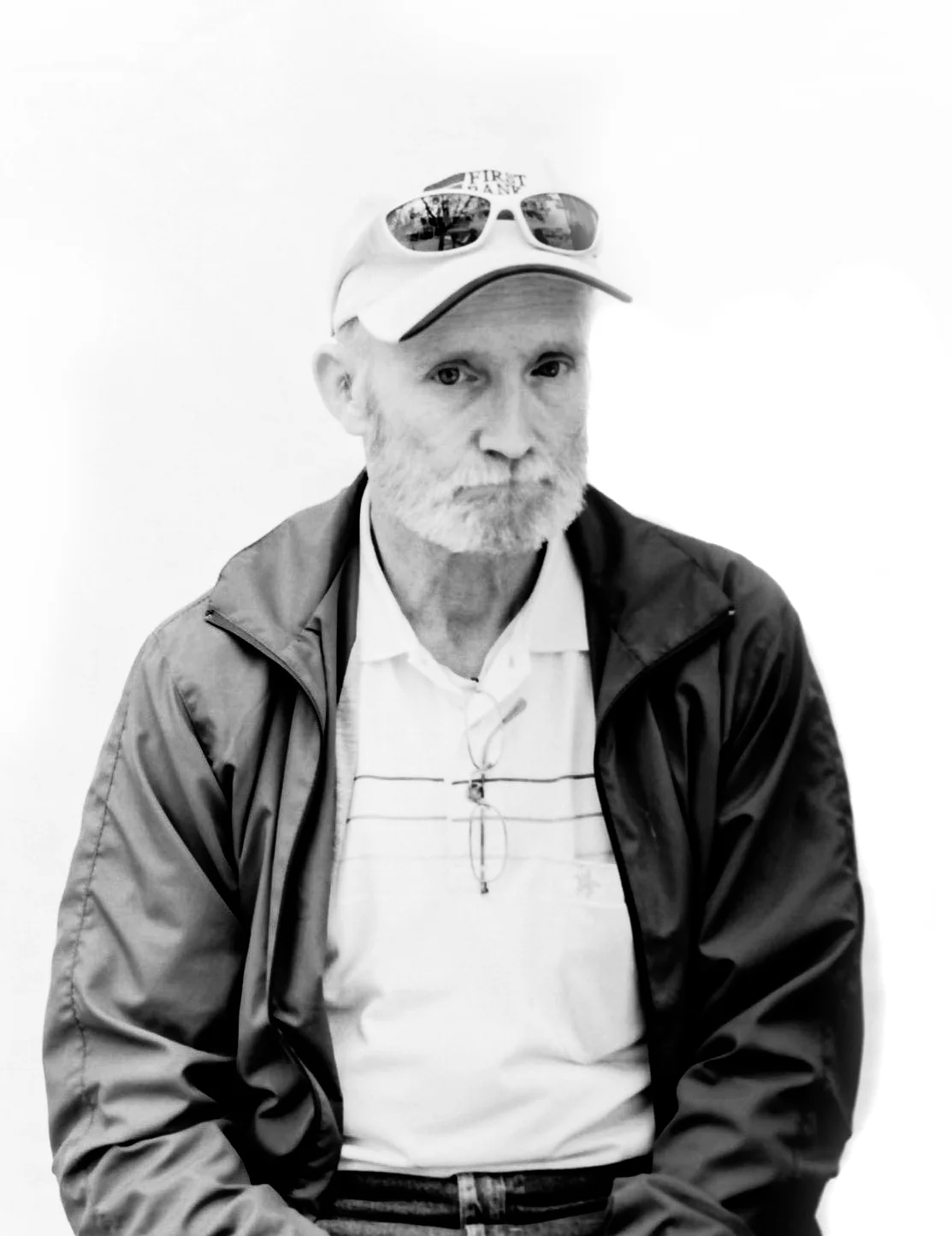

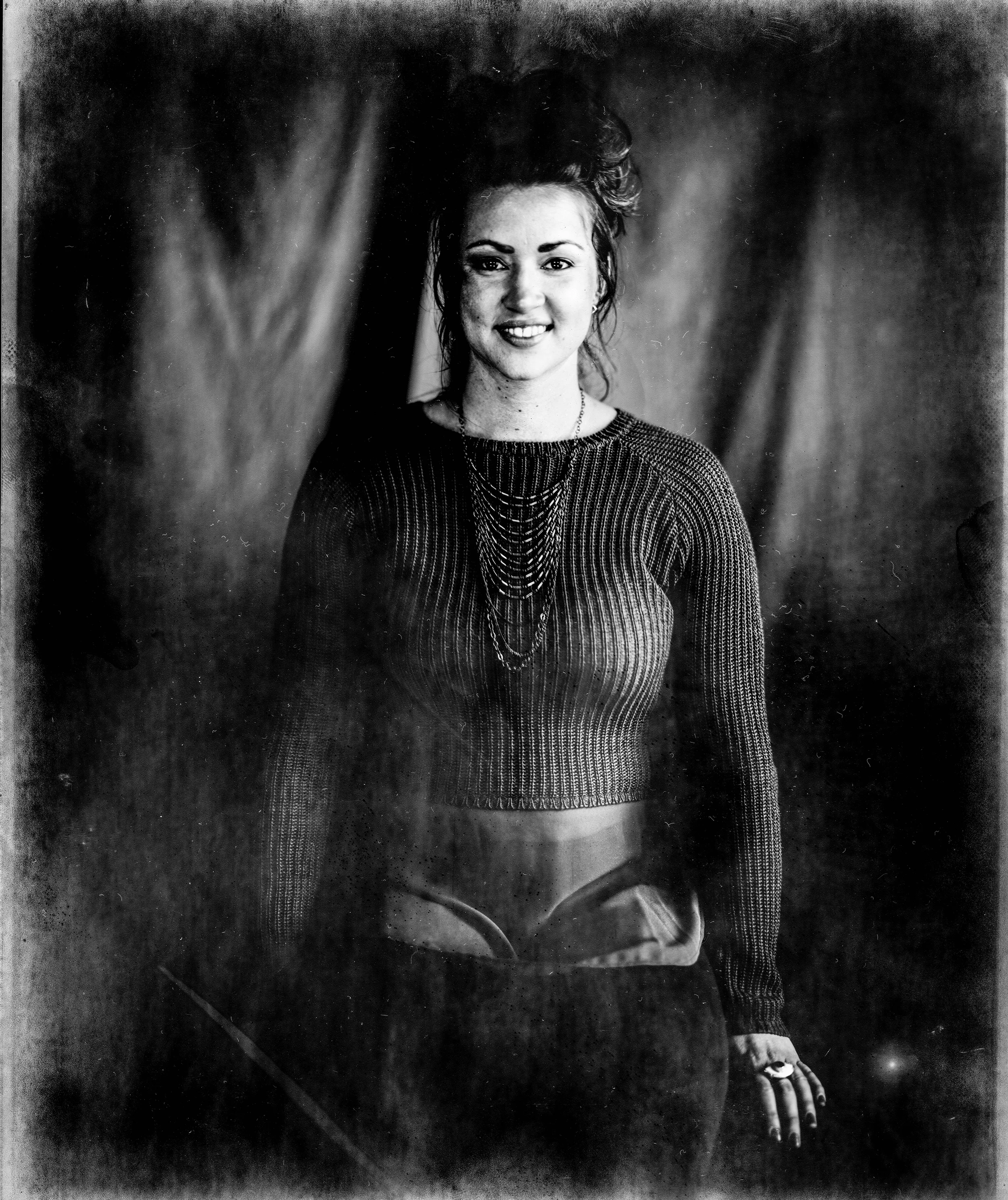

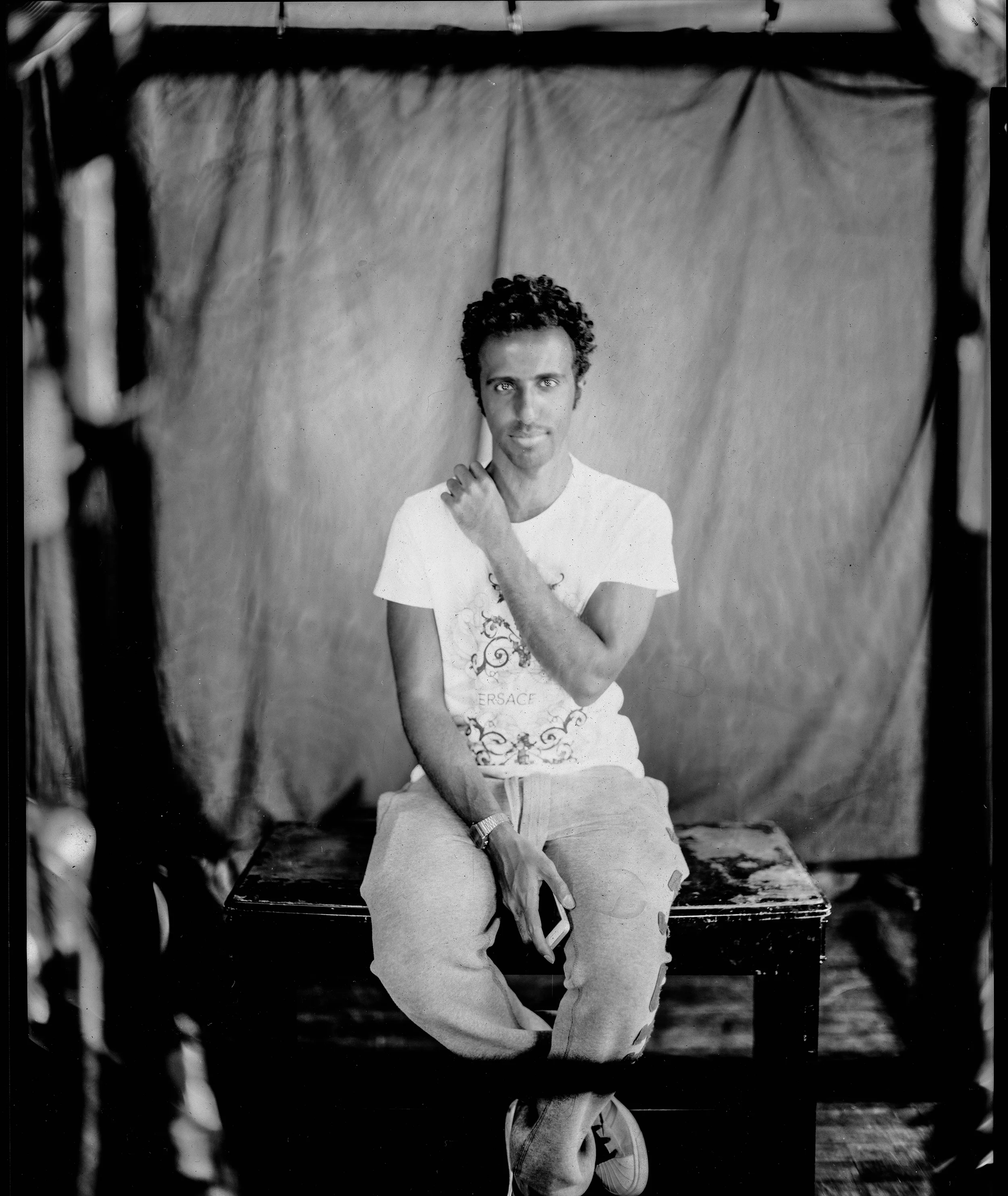

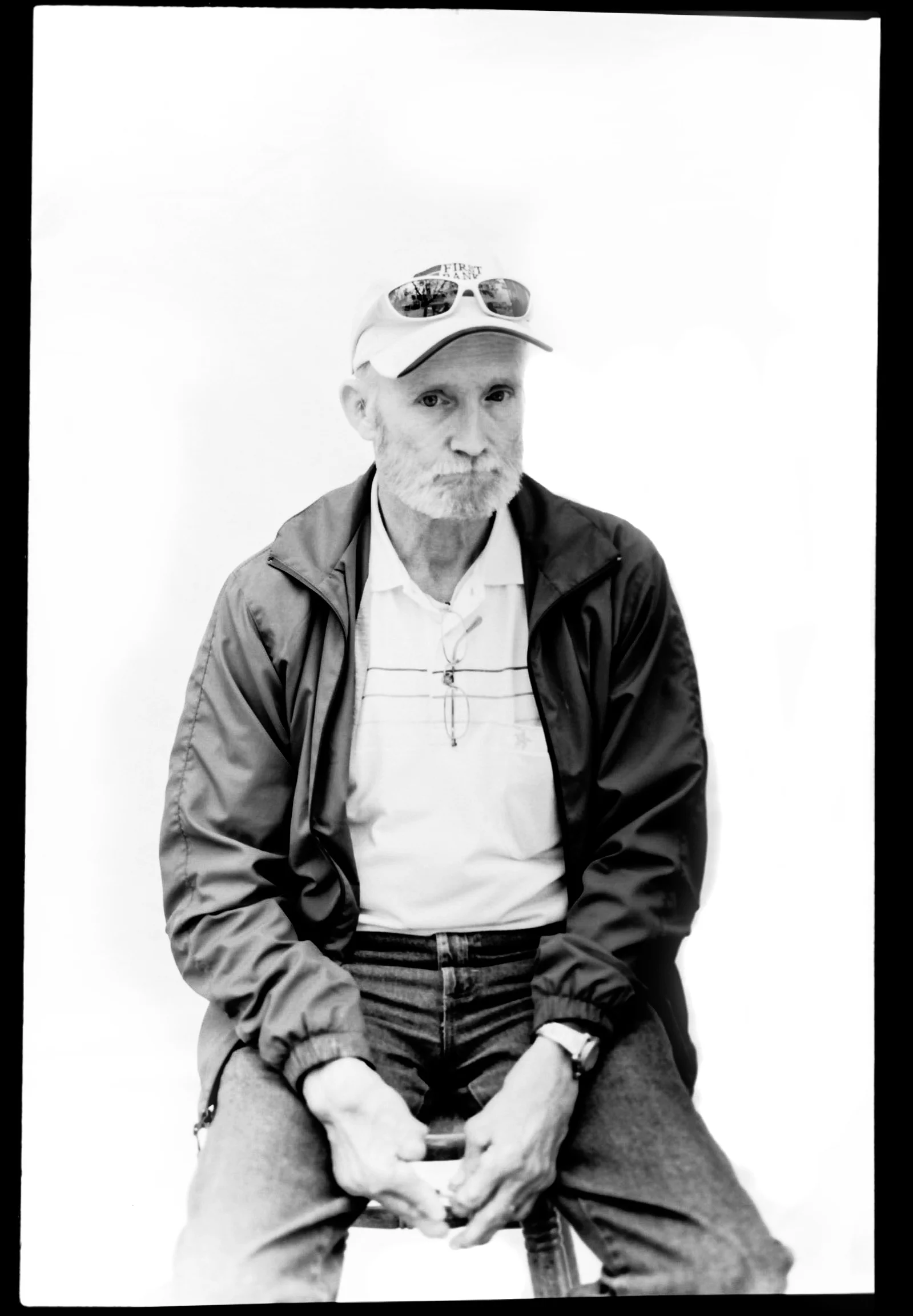

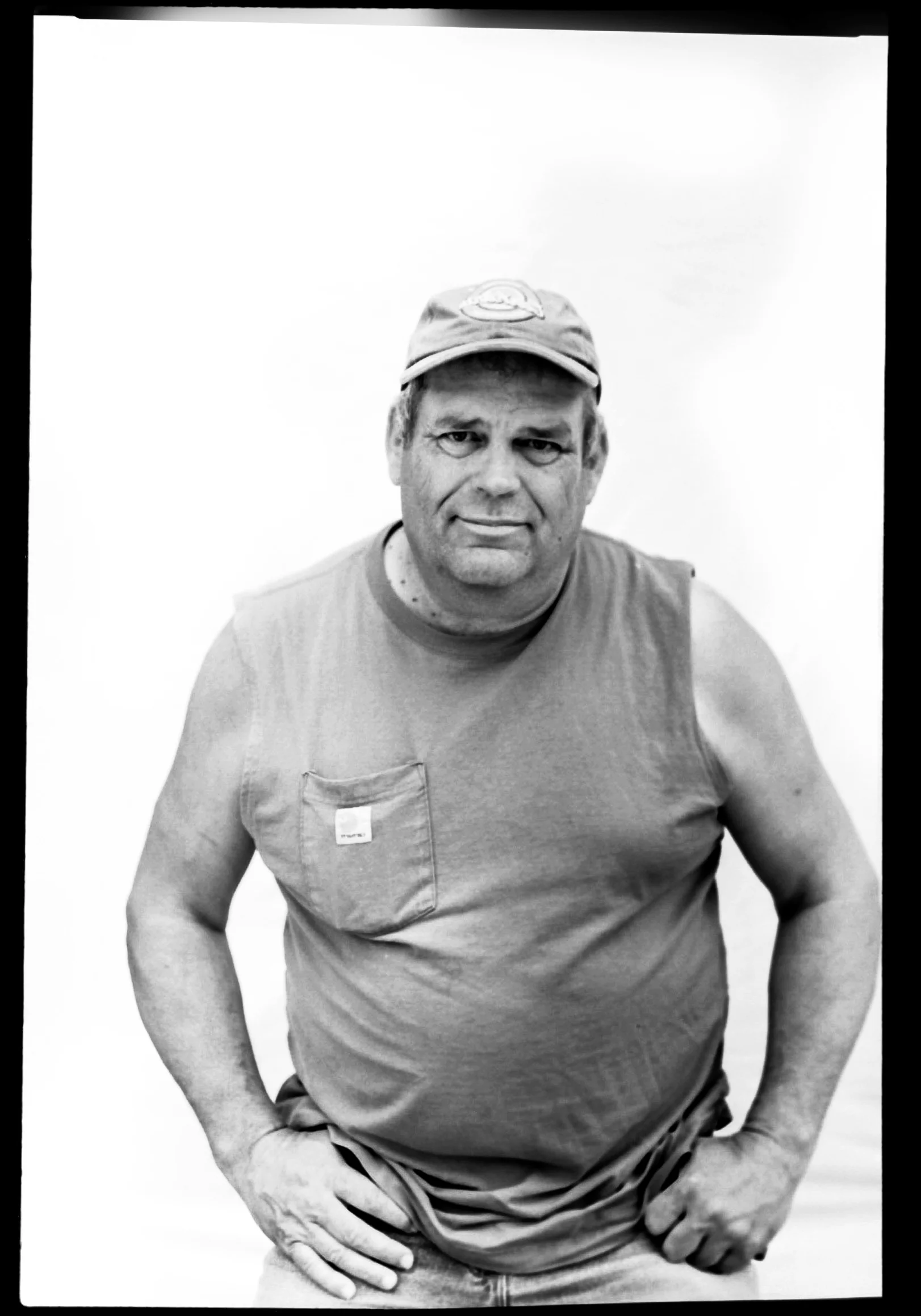

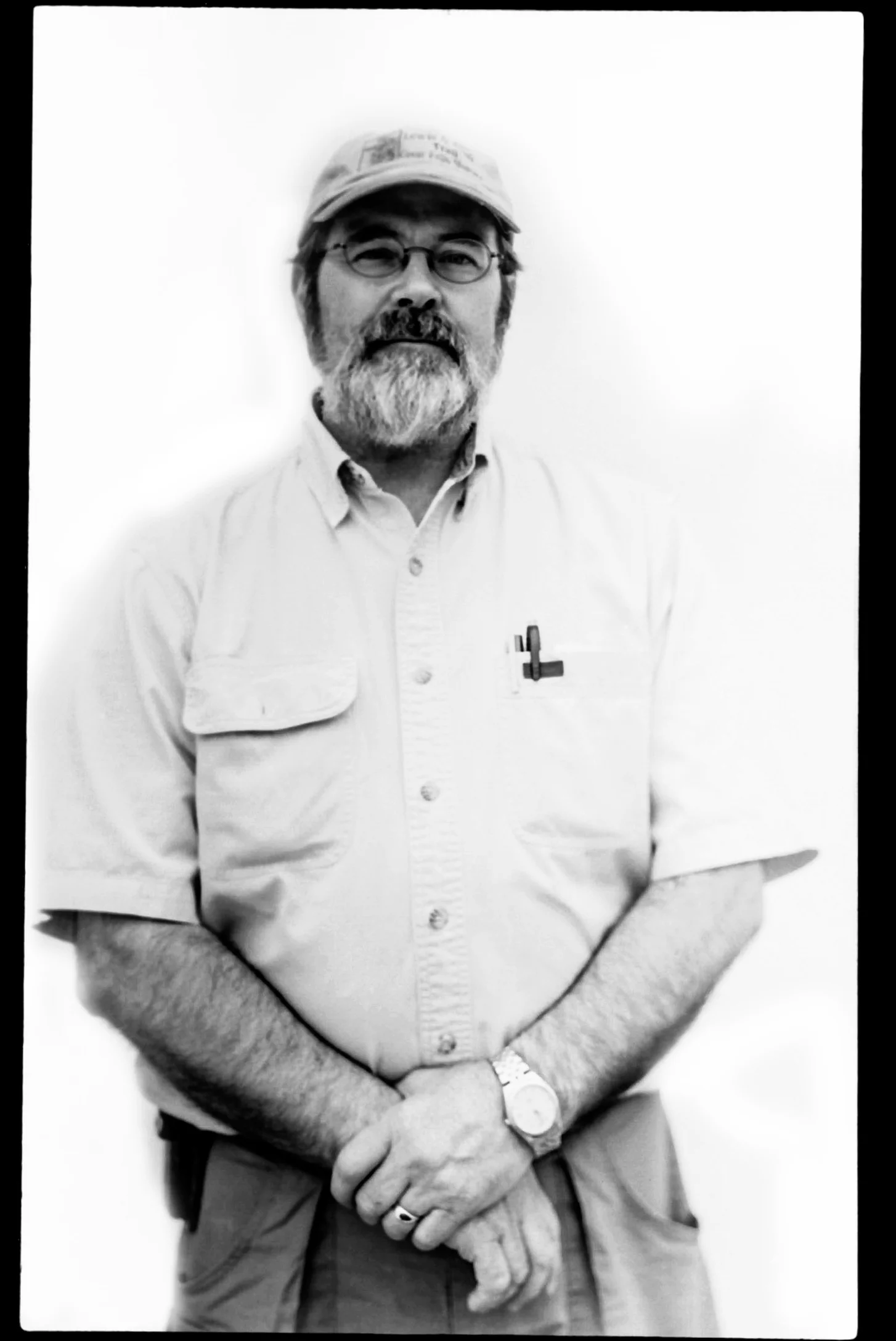

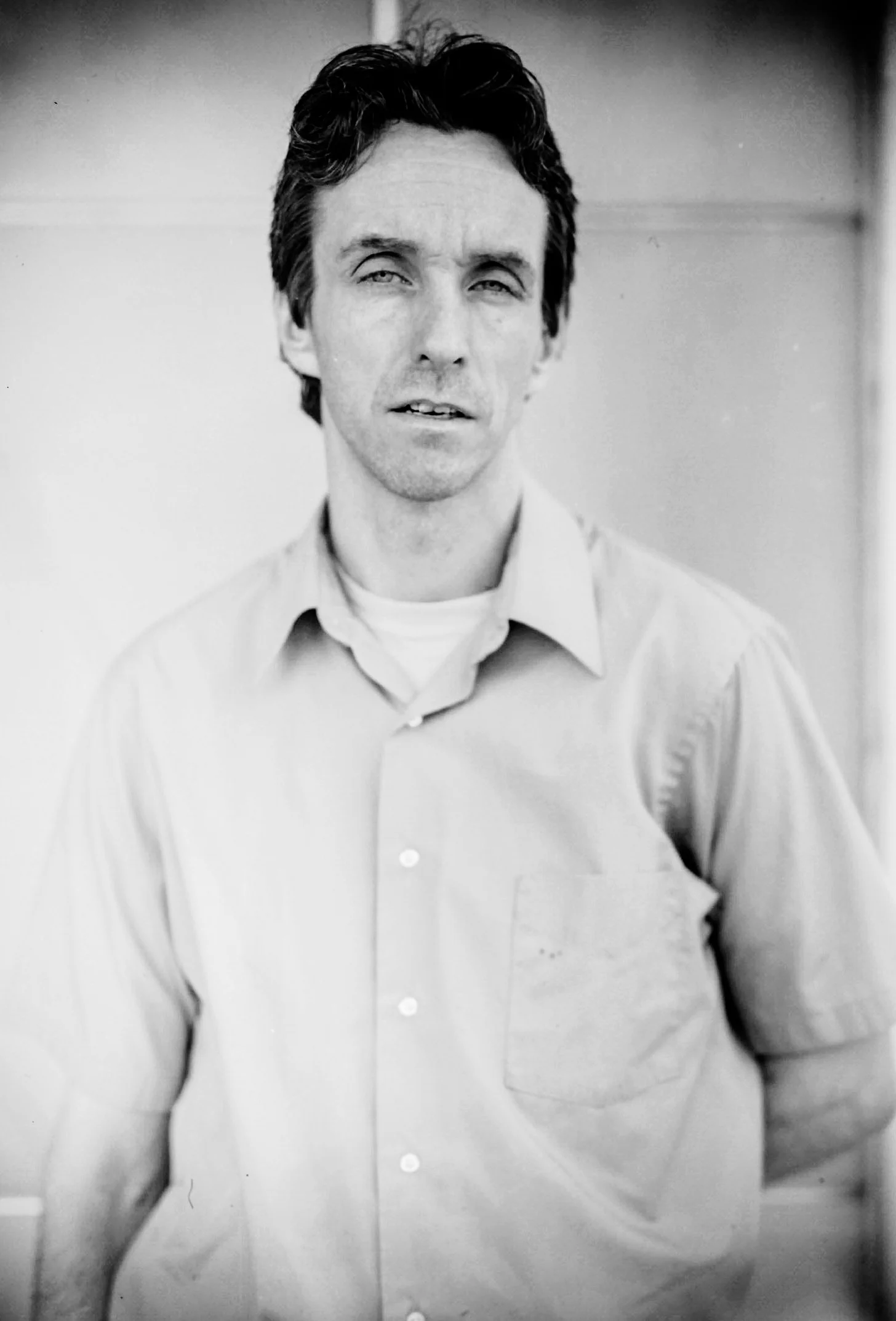

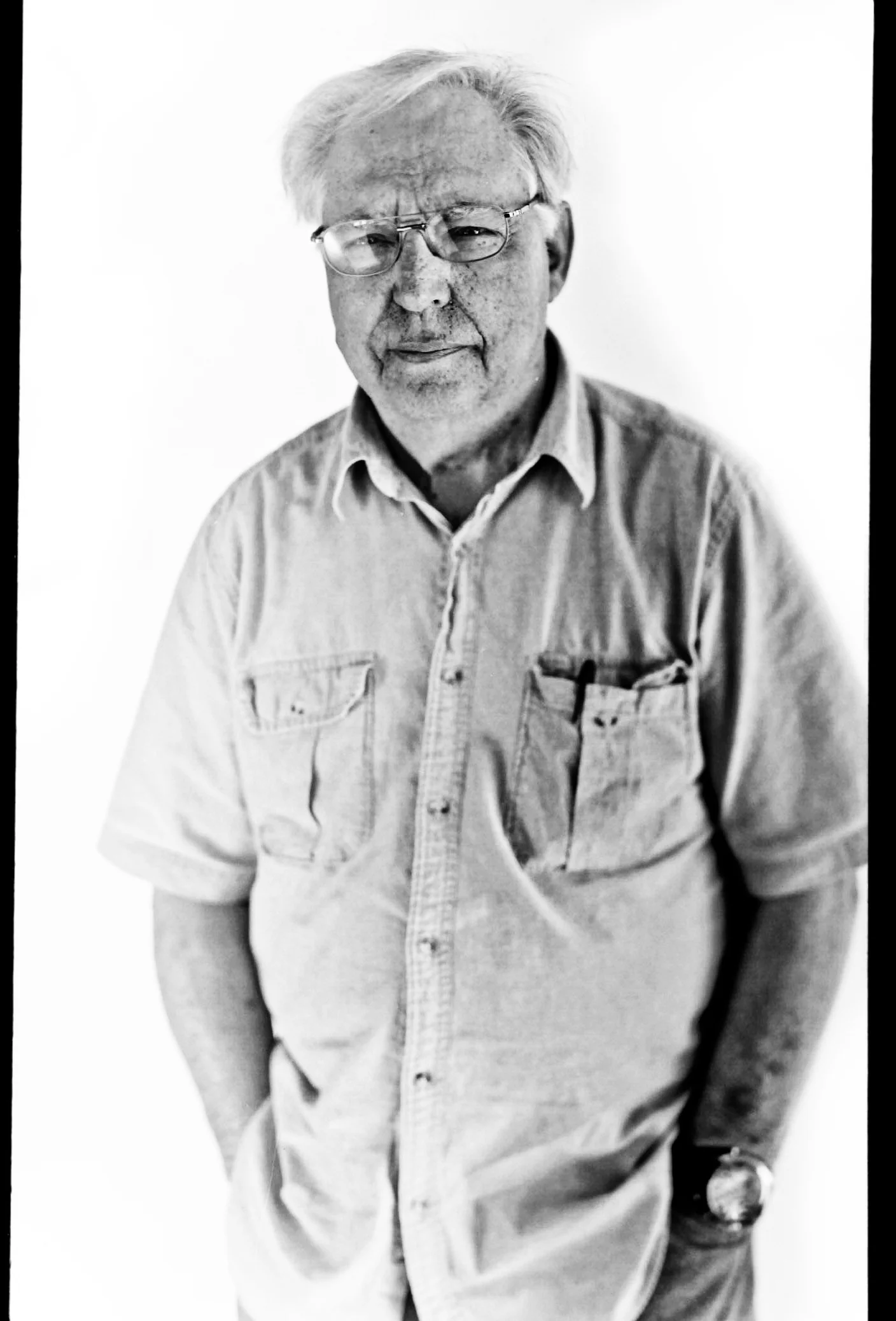

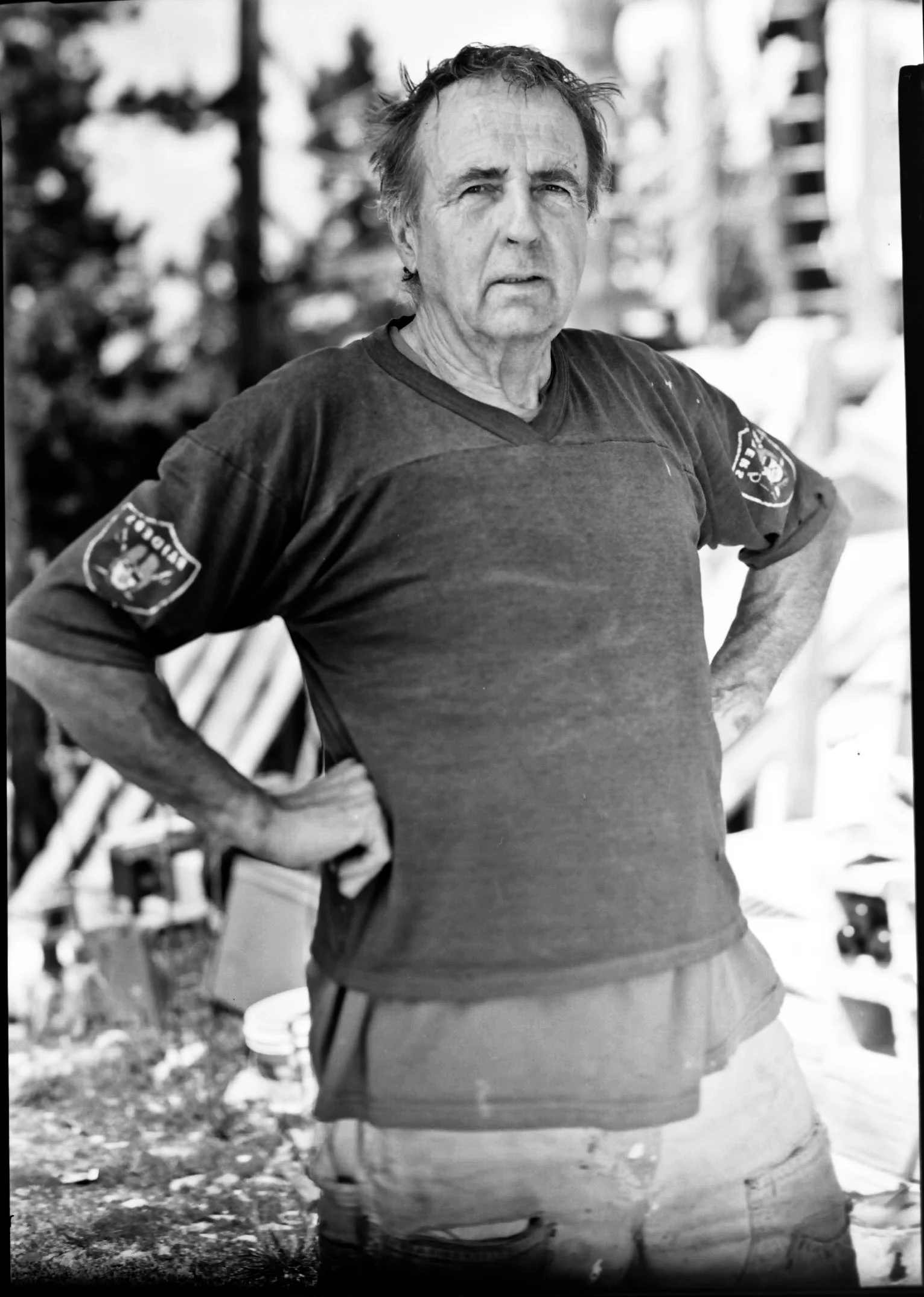

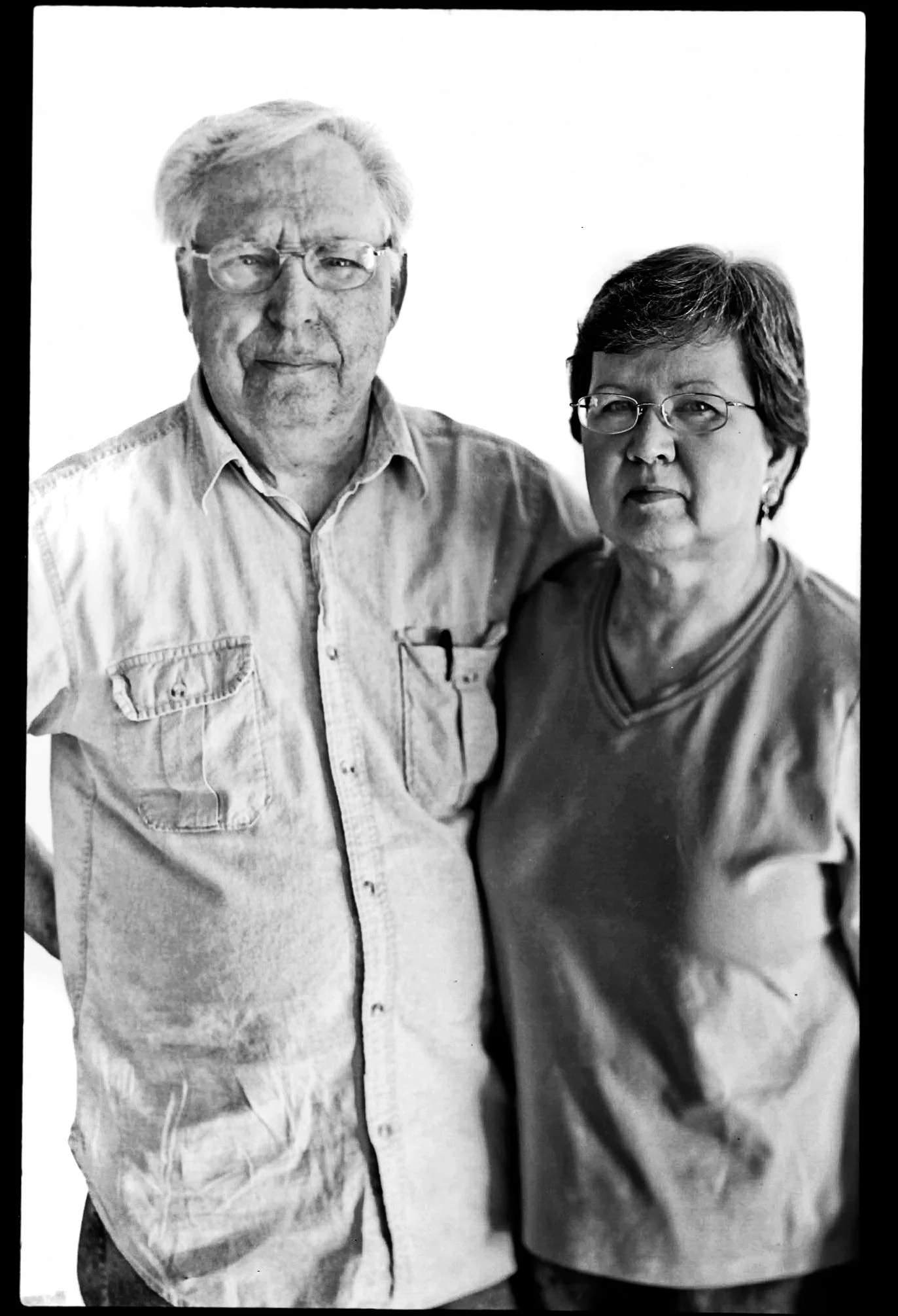

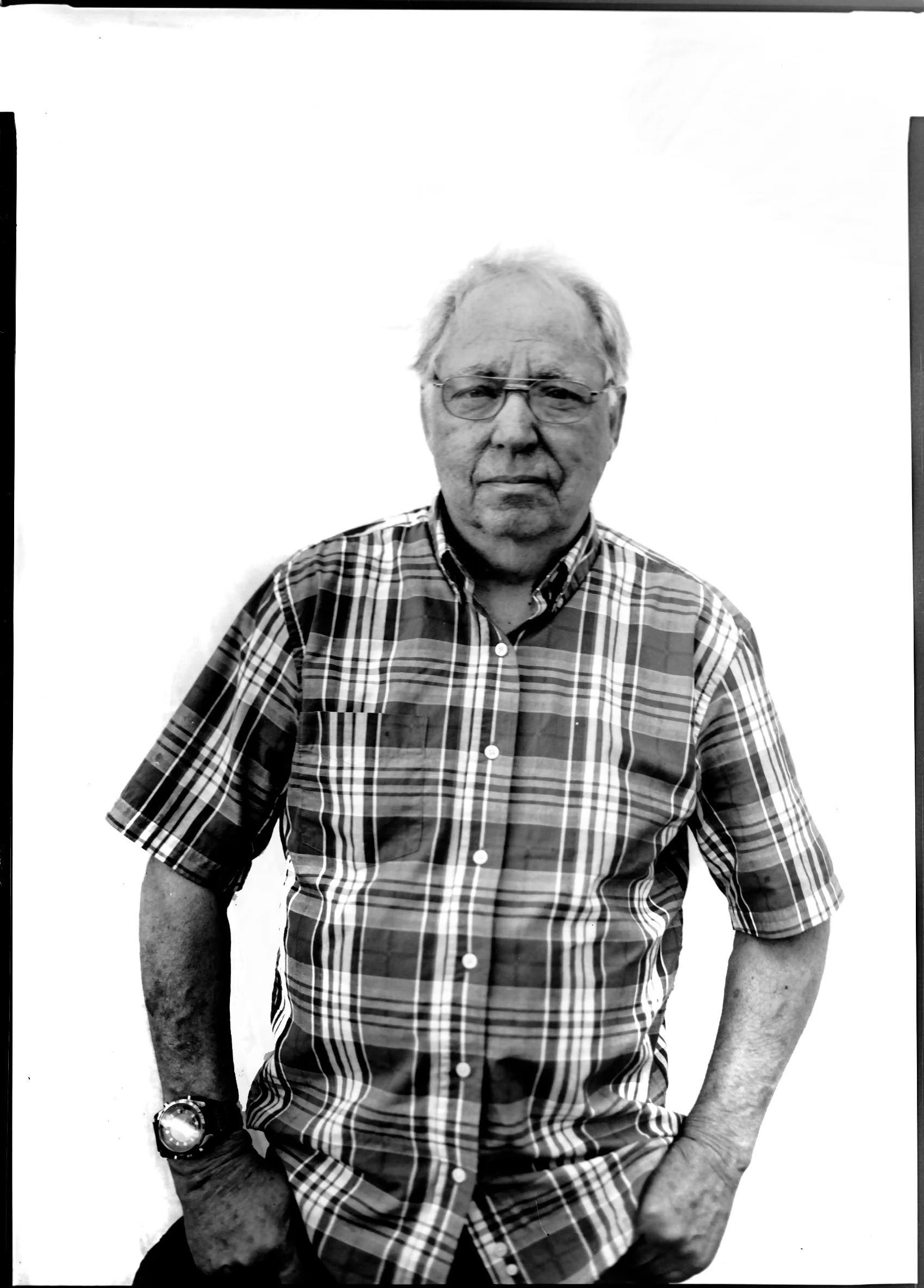

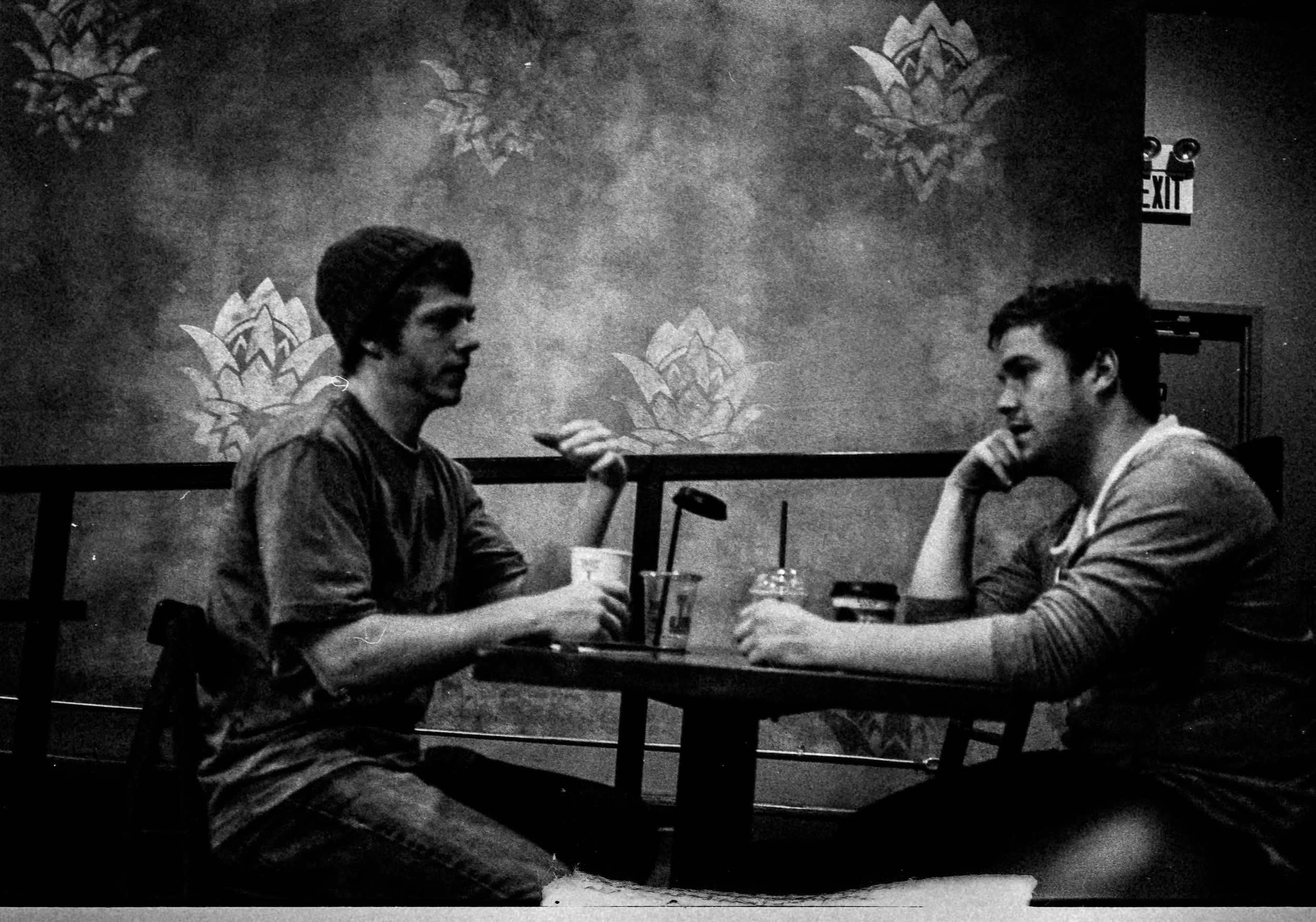

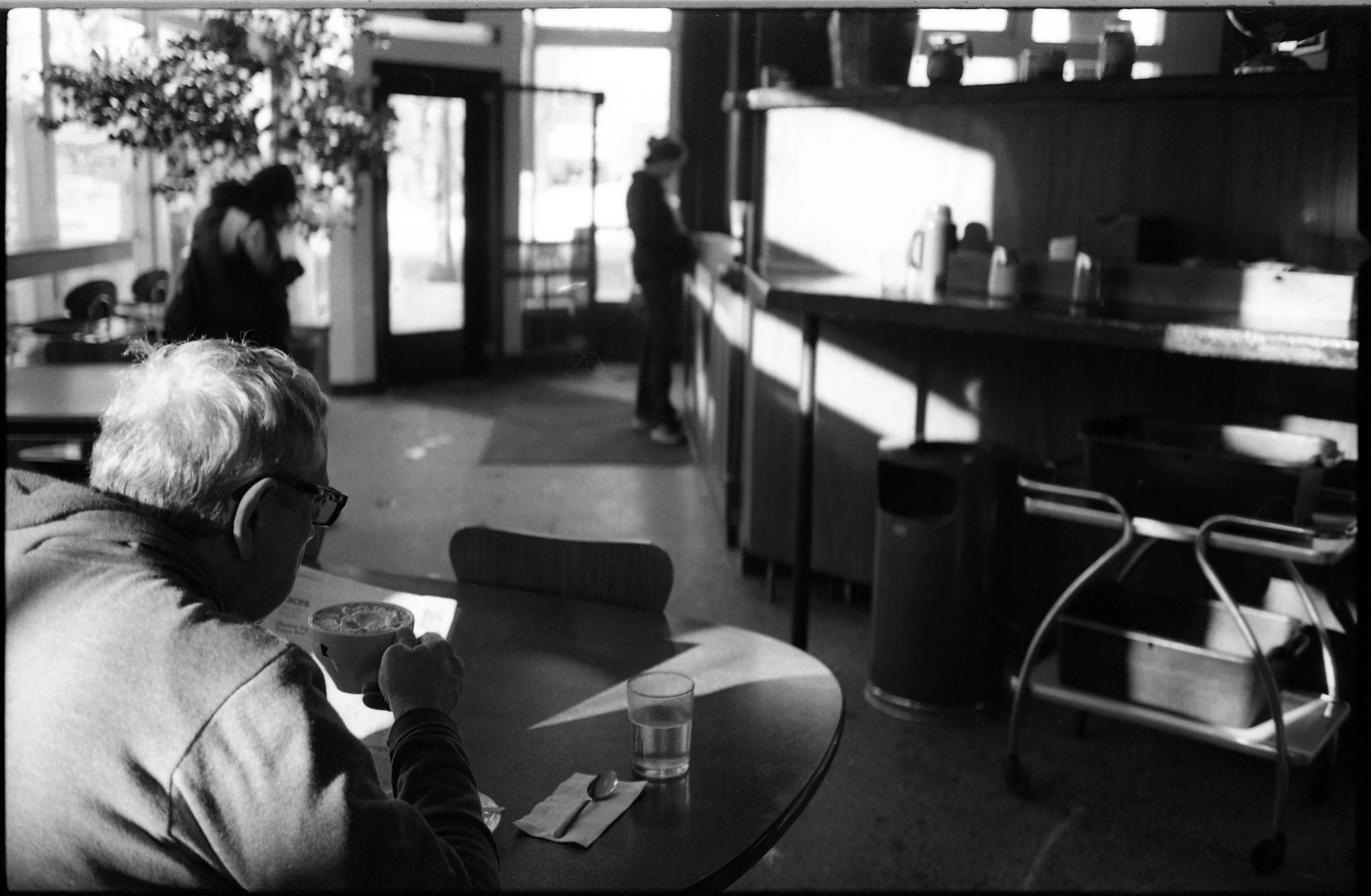

After many visits I developed a mythic belief that at some point there would be only a single living Italian remaining on from 1930’s Asmara, recalling nostalgically better times that everyday recede. I became determined to discover, and meet this fictional ‘last Italian.’ Census data revealed that of 75,000 Italians tallied in 1939, by 2008, only 900 remained. Over the course of four visits from 2002-2011, and given my white - outsider status - I was fascinated to come across these generally elderly Italian-Eritreans. Over the decade as such encounters dwindled, I witnessed a rich cultural affinity among my Eritrean contacts to all things Italian: the language, foods, customs, mannerisms, etc. Naively assuming Italian-Eritrean relations to be genial, I came to learn about the often negative influences that Italians had on the local population. Confronted by certain specific atrocities, I abandoned the project, nevertheless, it always retained a hold on my imagination.

Returning to Eritrea in 2012, I was unsuccessful in finding the figure I had so romanticized. Perhaps he no longer exists, or is hidden behind some closed door, busy in memories of past glory, while my camera has been unable to glimpse him. Or, he exists as a palimpsest, an erased figure whose traces remain in a wrought iron rail, or a light-strewn foyer. The current political state has made the likelihood of my own return questionable, and the last Italian in Asmara may pass into oblivion without mine, nor anyone else’s notice.